Institutionalizing Racial Bias as a Hate Crime in India: Constitutional Imperatives, Legislative Gaps, and the Supreme Court’s Contemporary Intervention

Syllabus: UPSC Prelims, GS II (Polity | Fundamental Rights | Social Justice | Hate Speech Jurisprudence)

Context:

Recently, the Supreme Court of India dealt with a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) seeking recognition of racial slurs and racially motivated violence as a distinct category of hate crime, particularly in the context of attacks on people from India’s North-East. The Court directed the petitioner to approach the Union Government through the Attorney General and observed that crimes based on race, language, appearance, or origin must be dealt with firmly.

The plea arose after the racially motivated assault and death of a student from Tripura (Anjel Chakma), where the attackers allegedly used racial slurs before the attack.

This issue raises a critical constitutional question:

Should India legally recognise racial slurs and racially motivated offences as “hate crimes”?

I. Introduction: From Racial Slur to Constitutional Question

The recent proceedings before the Supreme Court urging the Union Government to consider treating racial slurs and racially motivated offences as hate crimes mark a significant moment in India’s evolving constitutional jurisprudence on dignity, equality, and fraternity. What appears, at first glance, as a matter of criminal law classification is in fact a deeper constitutional inquiry into whether India’s legal system adequately recognizes identity-based harm.

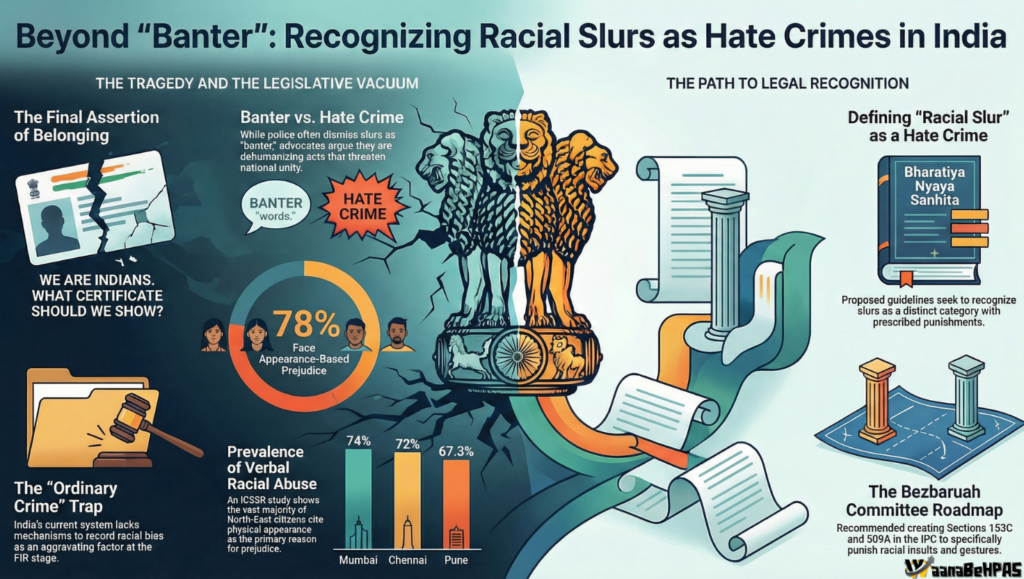

The issue gains particular urgency in the backdrop of the Anjel Chakma incident in Dehradun, where a young student from Tripura was allegedly targeted due to his North-Eastern features and subjected to racial slurs prior to fatal violence. His assertion — “We are Indians. What certificate should we show to prove that?” — encapsulates the constitutional crisis embedded in such crimes: the denial of equal belonging within the Republic.

When the legal system treats racially motivated violence merely as “hurt” or “grievous hurt” under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS), it risks reducing a constitutional wrong into an ordinary penal offence. This creates what may be termed evidentiary erasure, where the motive of bias — the core injury in a hate crime — disappears from legal recognition.

II. Supreme Court’s Intervention: Judicial Caution and Constitutional Sensitivity

In response to a Public Interest Litigation seeking recognition of racial slurs as hate crimes, the Supreme Court refrained from issuing immediate judicial guidelines but asked the petitioner to approach the Union Government through the Attorney General. The Court acknowledged the seriousness of identity-based targeting while simultaneously maintaining institutional restraint, emphasizing that the creation of new offence categories lies primarily within the legislative domain.

This approach reflects a calibrated constitutional balance:

- Recognition of rising racial discrimination concerns

- Judicial awareness of legislative vacuum

- Respect for separation of powers

At the same time, the Court’s observations that crimes based on race, appearance, or regional identity must be dealt with firmly indicate an implicit acceptance that India’s current legal framework is inadequate to address bias-motivated offences.

III. The Anjel Chakma Catalyst: A Symptom of Structural Constitutional Failure

The Chakma case is not an isolated criminal act but a manifestation of systemic legal inadequacy in addressing identity-based violence. Targeting based on racial appearance, followed by verbal dehumanization, reveals a pattern where prejudice operates as both precursor and aggravator of violence.

Yet, under the existing BNS framework:

- Section 115/117 (hurt/grievous hurt) ignore motive

- Section 196 (promoting enmity) requires a high threshold of group incitement

- Racial slurs are often trivialized as “banter”

Such classification dilutes the constitutional gravity of the act. In hate crimes, the injury is not merely physical; it is symbolic, collective, and constitutional. The victim is attacked not as an individual but as a representative of a community identity.

The failure to recognize this distinction amounts to a dereliction of the State’s parens patriae obligation to protect vulnerable citizens and uphold substantive equality.

IV. The Legislative Void: Deconstructing the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita (BNS) and the Hate Crime Gap

1. Absence of Legal Nomenclature

India currently lacks a statutory definition of “hate crime.” This absence is not merely semantic but jurisprudential. What remains unnamed often remains under-prosecuted.

Under the present framework:

| Offence | Current Legal Treatment | Recognition of Bias | Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Racially motivated assault | BNS Sections 115/117 | None | Motive erased |

| Racial slurs/verbal abuse | Section 196 (limited scope) | Indirect | Often dismissed |

| Hate crime (proposed) | Not codified | Mandatory bias recording | Enhanced sentencing |

The absence of a bias-recognition mechanism at the FIR stage results in systemic under-documentation of identity-based violence, weakening prosecution and sentencing.

V. Constitutional Framework: Articles 14, 15 and 21 in the Context of Hate Crimes

1. Article 14: Equality Before Law and Equal Protection

Racial targeting creates structural inequality. When similarly placed victims of ordinary crimes and bias-motivated crimes are treated identically under law, substantive equality is compromised. The law’s neutrality becomes a vehicle of injustice.

2. Article 15: Prohibition of Discrimination

Article 15 explicitly prohibits discrimination on grounds of race and place of birth. Violence accompanied by racial slurs against North-Eastern citizens directly implicates this constitutional guarantee.

Importantly, modern constitutional interpretation rejects a narrow reading of “on grounds only of.” Intersectional scholarship and jurisprudence emphasize that discrimination often operates through overlapping identities — race, region, appearance, and ethnicity.

3. Article 21: Right to Life with Dignity

The Supreme Court has repeatedly expanded Article 21 to include dignity, reputation, and psychological integrity. Racial slurs are not merely offensive speech; they constitute an assault on dignity and identity, thereby violating the right to live with dignity.

4. Preamble and Fraternity

Identity-based violence undermines fraternity, a foundational constitutional value. Fraternity ensures emotional integration of diverse identities within the nation-state. Racial dehumanization fractures this constitutional ethos.

VI. Hate Speech Jurisprudence and the Free Speech Balance

The debate around criminalizing racial slurs must be situated within Article 19(1)(a) and its reasonable restrictions under Article 19(2). The Supreme Court in cases such as Amish Devgan v. Union of India has drawn a distinction between:

- Free speech (criticism of policy, ideology)

- Hate speech (vilification of identity)

Criminalizing racial slurs does not suppress democratic dissent; rather, it protects group dignity and democratic participation. Speech that dehumanizes a racial or regional group threatens constitutional morality and social harmony.

VII. The Bezbaruah Committee (2014): A Blueprint for Reform

The M.P. Bezbaruah Committee, constituted after the Nido Taniam incident, remains the most authoritative institutional study on discrimination faced by North-Eastern citizens. Its recommendations remain largely unimplemented.

Key Proposed Legal Reforms:

- Section 153C: Criminalizing acts and gestures insulting a racial group

- Section 509A: Explicit penalization of racial slurs (up to three years imprisonment)

- Cognizable and non-bailable classification of such offences

Institutional Recommendations:

- Nodal police stations for immediate FIR registration

- Dedicated public prosecutors for racial discrimination cases

- Police sensitization training

- Institutional accountability mechanisms

These recommendations recognize racial discrimination as a criminal reality rather than a mere sociological concern.

VIII. Comparative Constitutional Perspective

International jurisdictions provide instructive models:

- United States: Bias motivation enhances sentencing under federal hate crime laws

- United Kingdom: Racially aggravated offences recognized statutorily

- Canada: Dignity-centric hate propaganda laws

Unlike these jurisdictions, India relies on fragmented provisions without a comprehensive hate crime framework, despite its deep diversity and history of identity-based exclusion.

IX. State-Level Innovation: Karnataka Hate Speech and Hate Crimes (Prevention) Bill, 2025

The Karnataka Bill offers a potential federal template through:

- Collective liability for institutional hate speech

- Internet content regulation to curb algorithmic amplification

- Narrow definition requiring intent and proximate harm

This model demonstrates that targeted legal regulation can coexist with free speech protections.

X. Vishaka Precedent and Judicial Role in Legislative Vacuum

Where legislative silence leads to violation of fundamental rights, the Supreme Court has historically intervened through guidelines, as seen in Vishaka v. State of Rajasthan. A similar interim framework defining hate crimes and racial slurs could be constitutionally justified until Parliament enacts formal legislation.

The judiciary, as the “sentinel on the qui vive,” bears a constitutional duty to safeguard dignity and equality when statutory frameworks are inadequate.

XI. Policy Imperative: Institutionalizing Racial Bias as an Aggravating Factor in BNS

A pragmatic rights-based reform must move beyond symbolic recognition toward enforceable statutory mechanisms.

1. Mandatory Recording of Bias Motivation (BNSS Amendment)

Police must be legally required to record bias indicators at the FIR stage. Investigative neutrality cannot mean investigative blindness to motive.

2. Racial Bias as an Aggravating Factor (BNS Amendment)

Inclusion of a general sentencing enhancement provision where racial, ethnic, or regional bias is proven. This would:

- Recognize societal harm

- Strengthen deterrence

- Align with international standards

3. Statutory Recognition of Racial Slurs

Racial verbal dehumanization should be codified as a distinct offence, acknowledging its role as a precursor to physical violence.

4. Institutional Oversight Mechanism

Creation of an Independent Hate Crime or Hate Speech Commission to:

- Monitor trends

- Ensure specialized prosecution

- Maintain national data on bias crimes

XII. Conclusion: From Formal Equality to Substantive Constitutional Justice

The Supreme Court’s recent engagement with the plea to treat racial slurs as hate crimes underscores a transformative constitutional moment. India’s criminal law framework, in its current form, remains ill-equipped to capture the constitutional injury inflicted by identity-based violence.

Treating racially motivated offences as ordinary crimes erases the very essence of discrimination and weakens the guarantees of Articles 14, 15, and 21. The institutionalization of racial bias as an aggravating factor within the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita is not merely a legislative reform; it is a constitutional necessity grounded in dignity, equality, and fraternity.

Until the law formally recognizes the gravity of racially motivated harm, the constitutional promise of equal citizenship will remain incomplete. A calibrated framework that protects free speech while criminalizing identity-based dehumanization represents the most coherent path toward substantive justice in a plural constitutional democracy.