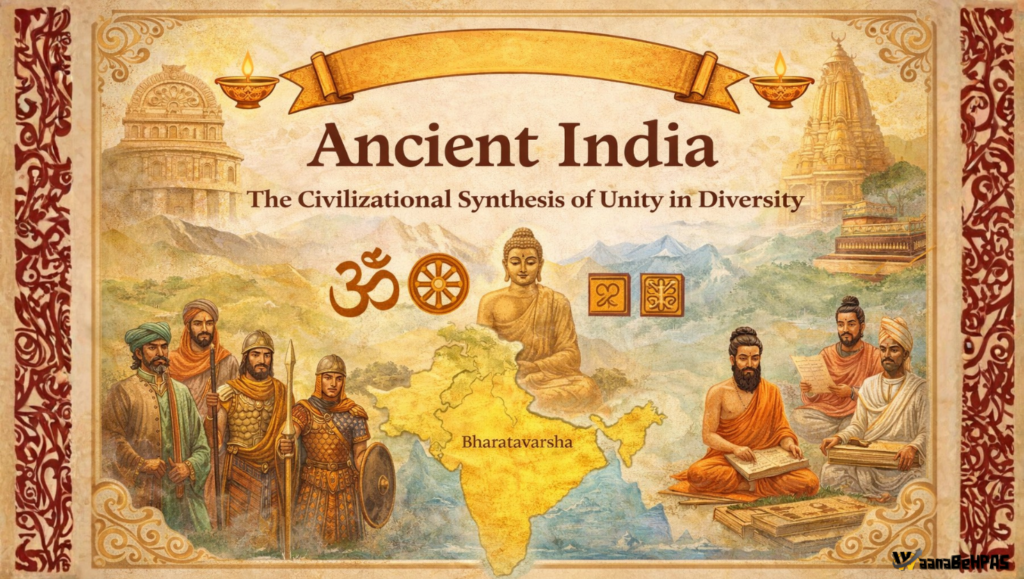

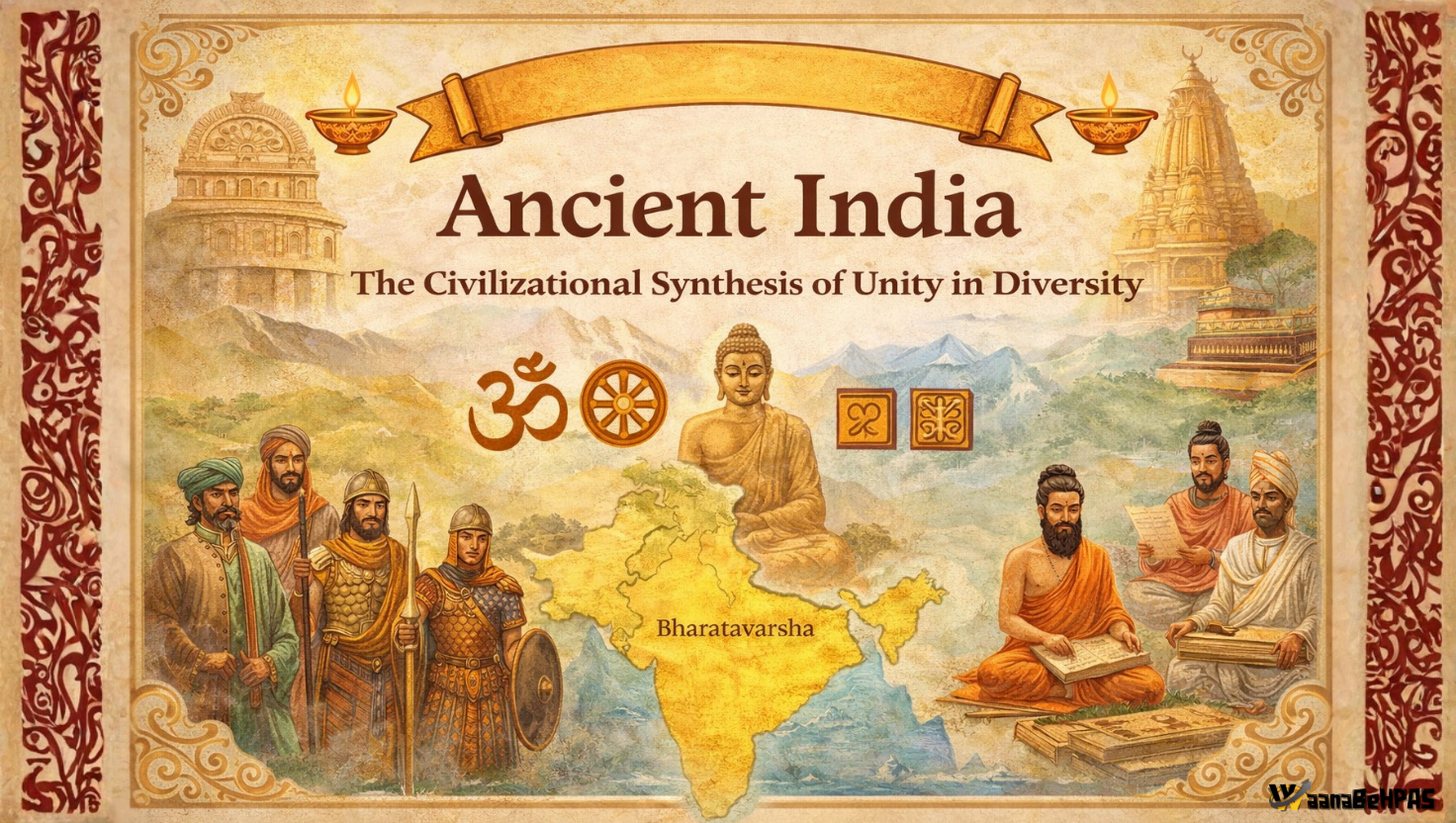

Ancient India: The Civilizational Synthesis of Unity in Diversity

Syllabus: UPSC GS-I (Ancient Indian History)

Introduction: Why Ancient Indian History Matters

The study of ancient Indian history transcends mere reconstruction of the past; it represents a strategic inquiry into the origins of one of the world’s most enduring civilizations.

This formative era explains how early communities moved from precarious subsistence to settled agrarian life through the mastery of natural resources and technological innovations such as agriculture, metal-working, spinning, and weaving. These developments enabled forest clearance, the establishment of villages, the rise of cities, and eventually the emergence of expansive political formations.

Equally significant is the genealogical role of antiquity in shaping India’s contemporary cultural landscape.

Modern scripts, languages, and literary traditions trace their roots to ancient prototypes, forming the intellectual scaffolding of Indian civilization.

This stable agrarian and linguistic base became the stage for a long historical process of:

- ethnic intermingling,

- religious pluralism,

- political integration, and

- social accommodation —

culminating in the civilizational ideal of unity amidst diversity.

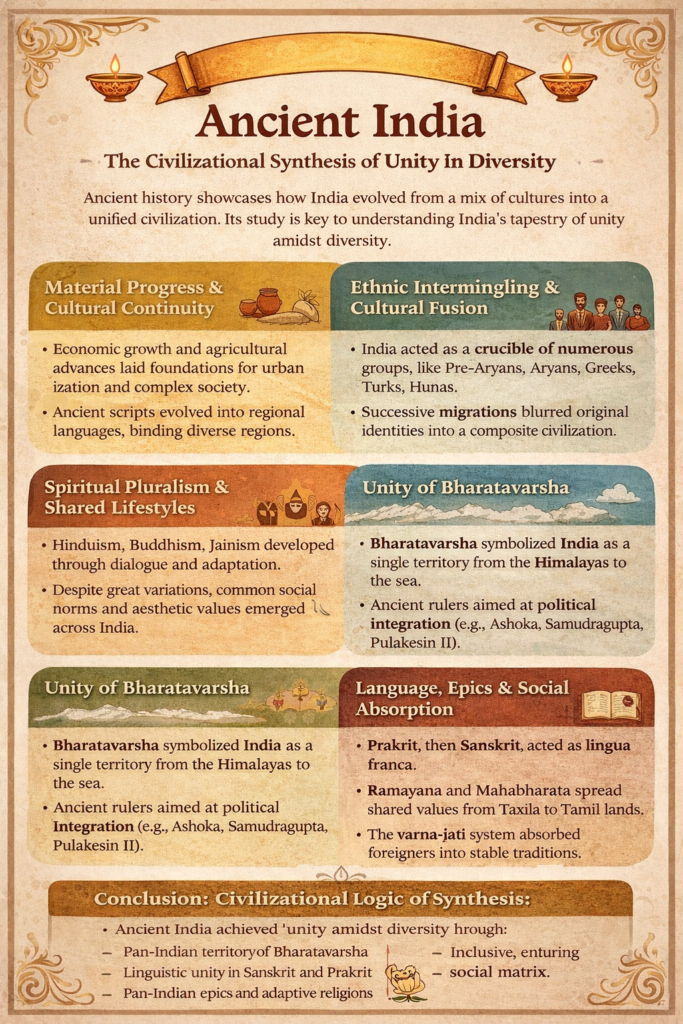

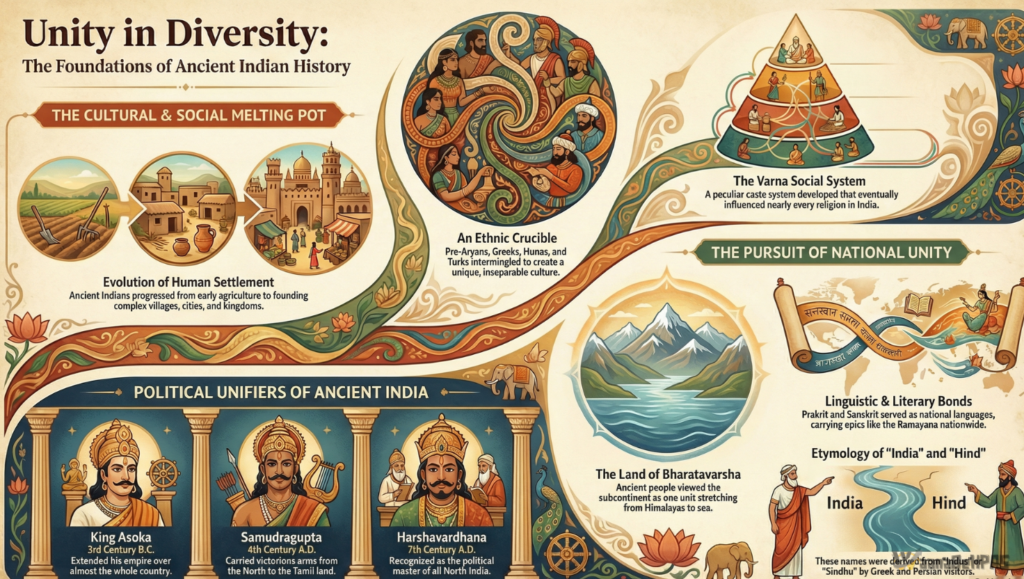

Early Material Foundations and Cultural Continuity

Ancient India’s economic transformation created the material conditions for complex society.

The domestication of crops, sophisticated craft traditions, and metallurgical advances expanded surplus production and trade networks.

Villages evolved into urban centers and imperial capitals, reflecting growing political authority and administrative sophistication.

Parallel to these developments was the emergence of writing systems and linguistic traditions.

The diverse scripts employed across India today evolved from ancient models, demonstrating striking cultural continuity.

Prakrit and Sanskrit acted as carriers of administrative authority and literary production, helping knit together geographically distant regions even during periods of political fragmentation.

A Crucible of Peoples: Ethnic Intermingling and Cultural Fusion

Indian civilization was not forged in isolation.

The subcontinent functioned as a “crucible of numerous races,” where successive streams of migration — Pre-Aryans, Indo-Aryans, Greeks, Scythians, Hunas, and Turks — gradually settled and became inseparable from the indigenous population.

Over centuries of cohabitation, their biological and cultural boundaries blurred, producing a composite civilization in which original identities were absorbed into broader social and cultural frameworks.

Each group contributed to linguistic evolution, artistic expression, political institutions, and religious thought, generating a dynamic yet stable civilizational core.

This continuous process of assimilation distinguishes Indian history from rigid civilizational models and provides a foundation for its remarkable longevity.

Spiritual Pluralism and Shared Cultural Patterns

Ancient India was the birthplace of Hinduism, Jainism, and Buddhism — traditions that developed not in isolation but through sustained dialogue, debate, and mutual influence.

These philosophical exchanges created shared ethical frameworks, ritual vocabularies, and social ideals.

Despite immense diversity in languages, sects, and customs, these interactions generated common styles of life visible in art, pilgrimage networks, educational institutions, and social practices across the subcontinent.

Such lived cultural unity preceded and often outlasted political unification, creating a civilizational coherence deeper than imperial control.

The later arrival of Christianity and Islam continued this historical pattern of interaction rather than rupture.

These traditions engaged existing social structures, producing hybrid practices and reinforcing India’s adaptive cultural grammar.

Bharatavarsha: Geographical Consciousness and Political Aspirations

Ancient Indians conceived of their land as a single geographical entity — Bharatavarsha — bounded by the Himalayas in the north and the seas in the south, from the Brahmaputra valley in the east to regions beyond the Indus in the west.

Poets, philosophers, and political theorists articulated this vision long before modern cartography.

Foreign observers echoed this unity through nomenclature derived from the Sindhu river, producing the terms India and Hind in Greek, Persian, and Arabic traditions.

Political thinkers translated this geographical imagination into the ideal of Chakravartin — the universal monarch.

Major attempts at subcontinental integration were undertaken by:

- Ashoka (3rd century BCE) under the Mauryas

- Samudragupta (4th century CE) during Gupta ascendancy

- Pulakesin II and Harshavardhana (7th century CE)

Although imperial unity was episodic, these efforts strengthened administrative networks, cultural diffusion, and economic integration across regions.

Language, Literature, and the Epics as Instruments of Integration

Linguistic cohesion acted as a civilizational adhesive.

In the 3rd century BCE, Prakrit functioned as a pan-Indian administrative language, evident in Ashokan inscriptions.

By the Gupta period, Sanskrit emerged as the principal language of governance and high culture — a status it retained even when political unity disintegrated in the post-Gupta age.

The great epics — the Ramayana and Mahabharata — further reinforced cultural coherence.

Studied from Tamil regions in the south to scholarly centers like Banaras and Taxila, these texts were translated into vernaculars without diluting their philosophical and ethical cores.

This ensured that the moral vocabulary of Indian civilization remained consistent despite regional linguistic diversity.

The Social Matrix: Varna, Absorption, and Institutional Durability

The evolution of the varna-jati system represented a distinctive mechanism of social organization.

Emerging initially in northern India, it gradually spread across the subcontinent, providing a framework for occupational specialization and social integration.

Rather than merely excluding newcomers, this system absorbed foreigners and migrants into existing social hierarchies, thereby stabilizing society during demographic change.

Even religious conversion often did not erase caste-based identities, revealing the extraordinary durability of ancient social institutions.

This capacity for assimilation allowed Indian society to preserve continuity while adapting to new cultural currents — a hallmark of its historical resilience.

Conclusion: The Civilizational Logic of Synthesis

Ancient Indian history records a long process of civilizational synthesis — the gradual fusion of ethnic, linguistic, religious, political, and social elements into a resilient and unified cultural world.

This unity was not imposed mechanically but constructed organically through:

- a shared geographical imagination of Bharatavarsha,

- linguistic bridges created by Sanskrit and Prakrit,

- pan-Indian literary traditions,

- adaptive religious pluralism, and

- social institutions capable of absorbing diversity.

For UPSC aspirants, this theme lies at the heart of GS-I and essay writing: India’s historical identity was forged not despite diversity, but through it.

The ancient past thus offers a powerful explanatory framework for understanding the continuity of Indian civilization into the modern age.