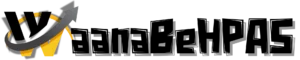

Approaches to the Modern History of India: A Historiographical Synthesis

Syllabus:- UPSC GS-I (Modern History)

1. Introduction: Understanding Historiography

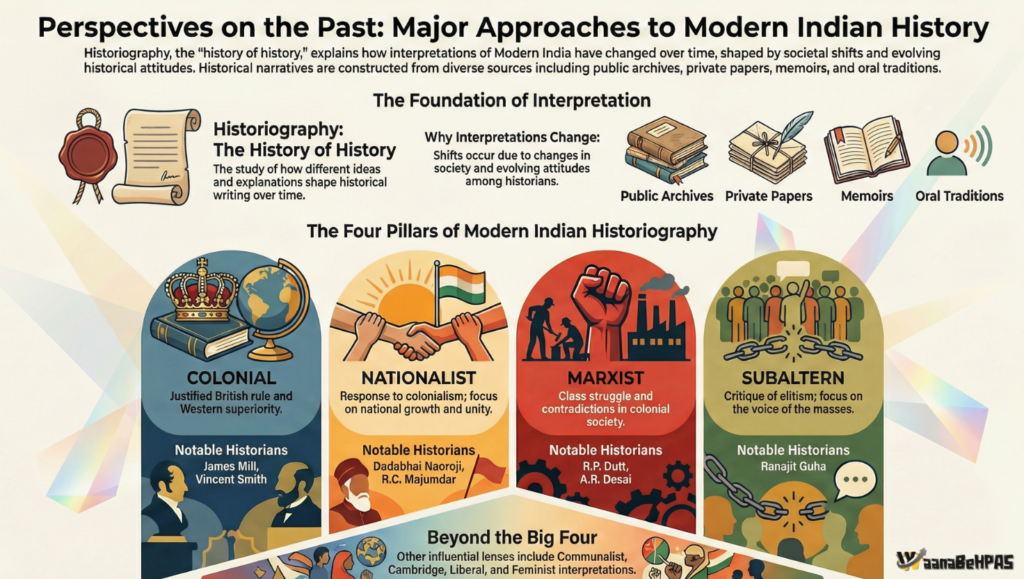

Historiography is more than a chronological record of events; it is the study of how history itself has been written, interpreted, and reinterpreted over time. To understand modern Indian history, a scholar must first engage with the intellectual frameworks that have shaped its narration. As Percival Spear observed, Indian historical writing has multiplied due to a “two-fold reason”: the rapidly changing Indian situation that demands fresh interpretation, and the evolving attitudes of historians toward what constitutes India’s essential past.

Thus, historiography provides the intellectual context that transforms history from static storytelling into critical inquiry. Every historical narrative is shaped by ideology, political interests, and social location. Recognizing these filters is essential for any serious study of the modern period, roughly spanning from the mid-eighteenth century to 1947.

2. The Colonial (Imperialist) Approach

Ideology and Purpose

The earliest dominant interpretation of modern India was produced by British administrators and scholars. The Colonial school was not a neutral academic exercise; it served to justify imperial domination. It portrayed British rule as a “civilizing mission” necessary to rescue India from alleged backwardness.

Core Features

- Orientalist Representation: Indian society was depicted as exotic, irrational, and static.

- Myth of Political Unity: Britain was credited with giving India its first real unity.

- Social Darwinism: The British claimed to be the “fittest to rule.”

- Stagnation Thesis: India was described as unchanging and in need of Western guidance.

- Pax Britannica: British law and order were presented as the sole protection against chaos.

Major Figures

James Mill, Mountstuart Elphinstone, and Vincent Smith were prominent exponents. The Revolt of 1857 was labeled a “mutiny,” and colonial exploitation was ignored.

Limitations

This approach denied Indian agency, overlooked economic drain, and reduced complex societies to stereotypes. Its hegemonic nature provoked the rise of nationalist counter-narratives.

3. The Nationalist Approach

Emergence as Counter-Narrative

Indian intellectuals responded to colonial writings by constructing a history centered on resistance and national unity. The aim was political as much as academic—to inspire anti-colonial consciousness.

Key Arguments

- British rule caused de-industrialization and poverty.

- The freedom struggle was a moral and united movement.

- Economic exploitation was exposed through the “Drain of Wealth” theory.

Contributors

- Nationalist Economists: Dadabhai Naoroji, R.C. Dutt, M.G. Ranade, G.K. Gokhale.

- Political Writers: Jawaharlal Nehru, Pattabhi Sitaramayya.

- Professional Historians (later): R.C. Majumdar, Tara Chand.

Strengths and Limits

The approach restored Indian perspective and demolished the Pax Britannica myth. Yet it often focused on elite leaders, neglecting peasants, workers, women, and internal social conflicts. This gap opened space for Marxist interpretations.

4. The Marxist Approach

Shift to Class Analysis

Marxist historians viewed colonialism as part of global capitalist expansion. They emphasized economic structures, modes of production, and class struggle rather than nationalist emotion.

Central Ideas

- Primary contradiction between colonial rulers and Indian people.

- Secondary contradictions among Indian classes.

- National movement seen as largely a bourgeois project.

Key Works

- Rajni Palme Dutt – India Today (1940)

- A.R. Desai – Social Background of Indian Nationalism (1948)

Desai traced the movement through phases supported by different social classes, shifting focus from “great men” to structural forces.

Criticism

Sumit Sarkar called early Marxist models “simplistic,” arguing that leaders often acted as proxies for passive masses. Economic determinism ignored culture, caste, gender, and popular consciousness.

5. The Subaltern Approach

History from Below

In the 1980s, Ranajit Guha and the Subaltern Studies collective challenged all earlier schools for their elitism. They argued that both colonial officials and nationalist leaders silenced the autonomous politics of ordinary people.

Features

- Focus on peasants, tribals, Dalits, women, workers.

- Use of oral traditions, folk memory, local archives.

- Nationalism seen as fragmented and contested.

Contribution

The Subaltern school democratized historiography by recognizing the independent agency of the masses and redefining “elite” to include both colonial and indigenous power holders.

6. Post-Colonial and Cultural Approaches

Recent scholarship studies colonialism as a cultural system shaping identities through education, language, law, and gender norms. It examines how power operated in everyday life and how Indians negotiated, resisted, and adapted to colonial modernity.

7. Comparative Overview

| School | Core Ideology | Interpretive Lens | Key Figures |

|---|---|---|---|

| Colonial | Justification of empire | Western superiority, Pax Britannica | James Mill, Elphinstone |

| Nationalist | Anti-colonial unity | Economic drain, heroic struggle | Naoroji, R.C. Dutt, Majumdar |

| Marxist | Class analysis | Capitalism & contradictions | R.P. Dutt, A.R. Desai |

| Subaltern | Voice of the marginalized | Elite vs people | Ranajit Guha |

8. Critical Takeaways for Researchers

- Multivocality: No single school captures the full reality of modern India.

- Source Criticism: Every document reflects the ideology of its creator.

- Diverse Evidence: Archives, memoirs, newspapers, and oral traditions must be combined.

- Interdisciplinary Reading: Economy, culture, caste, and gender must be studied together.

9. Conclusion

The historiography of modern India is a dialogue among competing perspectives. The Colonial school justified domination; the Nationalist school reclaimed dignity; the Marxists uncovered class structures; the Subalterns restored the voice of the marginalized; post-colonial studies explored culture and power. A balanced understanding emerges only when these approaches are read together.

Modern Indian history is therefore not a fixed story but an ongoing process of reinterpretation shaped by new questions and sources—from public archives in Delhi, London, and Lahore to private letters, biographies, and oral memories. The task of the historian is to navigate these perspectives critically and craft a narrative that reflects the complexity of India’s modern experience.