An Unholy Alliance: How the Jagat Seth Bankers and the East India Company Engineered the Conquest of Bengal

1.0 Introduction: The Tripartite Power Structure of 18th-Century Bengal

The mid-18th century was a period of profound transformation in Bengal, a region whose immense wealth and strategic importance made it the jewel of the declining Mughal Empire. The political landscape was not defined by a single, monolithic authority but by a complex and volatile interplay of three distinct powers. Understanding the triangular relationship between the weakening authority of the Nawab of Bengal, the vast financial influence of the Jagat Seth banking house, and the rising military-commercial ambitions of the British East India Company is crucial to comprehending the eventual conquest of the subcontinent. Each entity held a piece of the puzzle, and their shifting alliances would ultimately determine the region’s fate.

The three principal entities that shaped Bengal’s destiny were:

- The Nawab of Bengal: This office represented the regional governorship of the province, operating with significant autonomy since the death of Emperor Aurangzeb, when officials like Murshid Quli Khan consolidated power. Though nominally under the authority of the Mughal Emperor in Delhi, the Nawab was the de facto sovereign. In 1756, the throne was occupied by the young and assertive Nawab Siraj-ud-daulah, who was determined to curb the growing influence of foreign powers in his territory.

- The House of Jagat Seth: Known as the “powerful banker of Bengal,” this family-run financial institution was the veritable center of the region’s economy. Their control over credit, revenue collection, and minting gave them influence that rivaled, and in many ways exceeded, that of the political rulers. They were not merely bankers but indispensable pillars of the state’s financial architecture.

- The British East India Company: Initially a trading body granted special privileges by the Mughal court, the Company had evolved into an ambitious political and military force. Its principal possession at Fort William in Calcutta was a heavily fortified enclave from which it projected its commercial and, increasingly, its political power.

This analysis argues that the Battle of Plassey was not a military contest but the final, violent transaction in a corporate takeover, meticulously engineered and financed by the Jagat Seth banking house in collusion with the East India Company, effectively privatizing the state of Bengal. The British conquest was not a straightforward military victory achieved by a superior European force, but the direct outcome of a calculated conspiracy in which the Jagat Seths’ financial power was instrumentalized to orchestrate a political coup. To understand this dramatic political shift, we must first examine the seemingly symbiotic commercial relationship that initially bound the bankers and the Company together.

2.0 A Symbiosis of Commerce and Capital: The Early Relationship

In the pre-industrial era, the expansion of the East India Company’s commercial operations was fundamentally dependent on its ability to access local capital. The financial mechanisms of 18th-century Bengal provided the liquidity necessary for the Company to purchase goods, finance voyages, and maintain its establishments. Without a reliable source of credit and financial services within India, the Company’s growth would have been severely constrained, making an alliance with the region’s most powerful indigenous financial institution not just advantageous, but essential.

The early relationship between the House of Jagat Seth and the East India Company was built on a foundation of commercial symbiosis. As the historical record explicitly states, the “Jagat Seth house of Indian bankers financed much of the East India Company’s business in Bengal.” This arrangement served the interests of both parties. For the Jagat Seths, financing the burgeoning trade of a major European company provided a lucrative and reliable stream of revenue, allowing them to diversify their financial activities and solidify their position as the indispensable financiers for all major economic players in the region.

For the East India Company, the benefits were even more critical. Relying on the Jagat Seths provided them with immediate access to vast sums of local currency, bypassing the logistical difficulties and risks of shipping large quantities of bullion from Europe. This partnership lubricated the wheels of their trade, enabling them to operate on a scale that would have otherwise been impossible. This financial dependency, while commercially convenient for the Company, created a strategic vulnerability for the Nawab’s regime, as Bengal’s premier financial institution was now deeply invested in the success of a foreign power. As the political climate in Bengal grew more turbulent, this relationship of convenience would be tested, ultimately transforming from a commercial partnership into a clandestine political alliance.

3.0 The Spark of Conflict: Siraj-ud-daulah and the English

The open conflict that erupted between Nawab Siraj-ud-daulah and the East India Company in 1756 was not a sudden clash but the culmination of escalating tensions over issues of sovereignty, trade privileges, and political influence. The Nawab viewed the Company’s “highhandedness” and its increasing fortification of Calcutta as a direct challenge to his authority. Grievances had a clear financial basis; a 1651 agreement with Nawab Shuja-ud-din permitted the Company its trading activities in exchange for an annual payment of ₹3,000, a sum the increasingly powerful Company chafed at. The final spark was the Company’s decision to grant protection to Krishna Das, an enemy of the Nawab, an act of political defiance Siraj-ud-daulah could not ignore.

The key events that led to open hostilities unfolded in rapid succession:

- The Attack on Calcutta (June 1756): Determined to punish the Company, Siraj-ud-daulah marched on its headquarters, striking Calcutta on June 16, 1756. By June 20, the city and Fort William were under his control.

- The Recapture of Calcutta (January 1757): The English regrouped and retaliated. A force led by Robert Clive attacked and recaptured Calcutta in January 1757.

- The Treaty of Alinagar: Following this defeat, Siraj-ud-daulah was compelled to sign the Treaty of Alinagar on February 9, 1757, in which he was forced to agree to all of the Company’s claims.

It was during the Nawab’s initial capture of Fort William that the notorious episode of the “Black Hole of Calcutta” is said to have occurred. This narrative originated from the sole contemporary account of a survivor, John Zephaniah Holwell, who claimed 123 British prisoners died overnight in a small dungeon. Though its details are now almost universally considered to be greatly embellished—Indian scholars have shown the Nawab had no hand in this affair, and that the number of incarcerated prisoners was no higher than 69—the story became a powerful propaganda tool. It was used to represent “Indians as a base, cowardly, and despotic people,” fueling British public anger and justifying a more aggressive stance against the Nawab. Having regained their military and commercial position, the English were no longer content with simply defending their interests; they now actively sought to replace Siraj-ud-daulah with a ruler more compliant to their ambitions.

4.0 The Conspiracy of Plassey: A Financially-Backed Coup

With their position in Calcutta restored, the leadership of the East India Company made a strategic pivot. They transitioned from a commercial body defending its privileges to a political entity actively engineering a regime change. This ambitious goal was not to be achieved through sheer military might, which they lacked, but through the time-honored tools of conspiracy and alliance-building. By identifying and partnering with disaffected elites within the Nawab’s own court, the Company planned to orchestrate a coup d’état that would place a puppet on the throne of Bengal.

The conspiracy to overthrow Siraj-ud-daulah was a coalition of powerful local figures who felt their interests were threatened by the young Nawab. The key conspirators included:

- Mir Jafar: The commander-in-chief of the Nawab’s army.

- Rai Durlab: Another high-ranking commander in the Nawab’s forces.

- Jagat Seth: The powerful banker of Bengal, whose financial backing was indispensable.

- Omi Chand: A rich merchant involved in the court’s commercial dealings.

The Jagat Seths’ role transcended that of mere conspirators; they were the venture capitalists of a regime change, leveraging their financial power to underwrite the entire military operation and ensure its success. The historical record reveals that the Jagat Seths helped finance the “company’s military campaign of 1757,” thereby directly enabling the military action that would serve as the public face of this internal betrayal. By providing the capital for Clive’s army, the bankers transformed a political conspiracy into a viable military operation, setting the stage for a confrontation that was decided long before the first shot was fired.

5.0 The Battle of Plassey (1757): The Alliance Triumphant

The Battle of Plassey, fought on June 23, 1757, is often portrayed as a heroic and decisive military victory that secured British dominance in India. However, a closer examination reveals it “was not a battle in the real sense” but rather the physical execution of the meticulously planned conspiracy. The outcome was pre-determined not on the battlefield, but in the secret negotiations between the English and the Nawab’s treacherous commanders.

On the day of the battle, the Nawab’s vastly superior army faced a small contingent of English soldiers under Robert Clive. However, the largest and most critical sections of the Nawab’s army were commanded by Mir Jafar and Rai Durlabh. Having already “shifted their allegiance towards the English,” these commanders “made no effort to contest the English troops.” With the bulk of his army standing idle, Siraj-ud-daulah’s defeat was inevitable. He was subsequently captured and killed, and Clive promptly installed the chief conspirator, Mir Jafar, on the throne of Bengal.

The conspiracy’s success immediately pivoted the East India Company from a commercial enterprise to a kleptocratic state, yielding rewards that were both immediate and immense.

| Reward | Description |

| Financial Plunder | Mir Jafar was forced to pay a “huge sum to the English” for their services. The sheer scale of this wealth transfer is illustrated by the fact that “almost 300 boats were required to carry the spoils to Fort William.” |

| Territorial Gains | As part of the arrangement, Mir Jafar ceded the zamindari (land revenue rights) of the 24 Parganas, a large and valuable territory, directly to the English. |

The victory at Plassey was more than just a successful coup; it was the moment the East India Company seized the levers of political and financial power in Bengal. The immediate spoils were staggering, but the long-term strategic transformation of the Company from a trading entity into a territorial empire was the true prize.

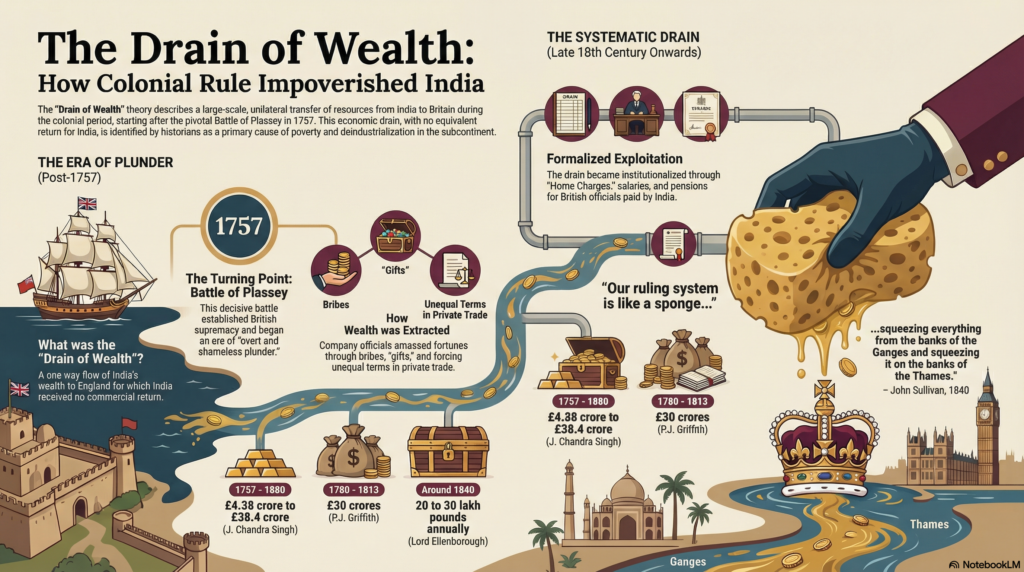

Infographics

6.0 Conclusion: From Financiers to Kingmakers and the Dawn of Empire

The calculated alliance between the East India Company and the House of Jagat Seth stands as a pivotal turning point in Indian history. What began as a relationship of commercial convenience, with the bankers financing the Company’s trade, evolved into a political conspiracy that toppled a kingdom and laid the groundwork for two centuries of colonial rule. The events culminating in the Battle of Plassey were not an accident of history but the deliberate result of shared interests between an ambitious foreign power and aggrieved local elites.

The long-term consequences of the alliance’s triumph at Plassey were profound. The victory marked the “beginning of EIC political domination,” irrevocably transforming the Company from a commercial enterprise into a de facto sovereign power. With a puppet Nawab on the throne and direct control over vast revenues, the Company was able to fund further military expansion and consolidate its hold not just on Bengal, but eventually across the entire subcontinent. The plunder of the treasury was merely the prelude; the subsequent establishment of a “Dual Government” system would institutionalize this plunder, bleeding Bengal’s economy dry to finance the Company’s imperial ambitions. The Jagat Seths, in their role as kingmakers, had unleashed a force they could not control.

The conspiracy of 1757 serves as a stark illustration of how indigenous financial power, when allied with foreign military ambition, could reshape the political destiny of a nation. In pursuit of their own immediate interests—securing their wealth and influence against a hostile Nawab—the Jagat Seths and other local elites facilitated the ascent of a foreign power. This unholy alliance, born of finance and forged in conspiracy, ultimately engineered the conquest of Bengal and marked the true dawn of the British Empire in India.